DEHP Exposition

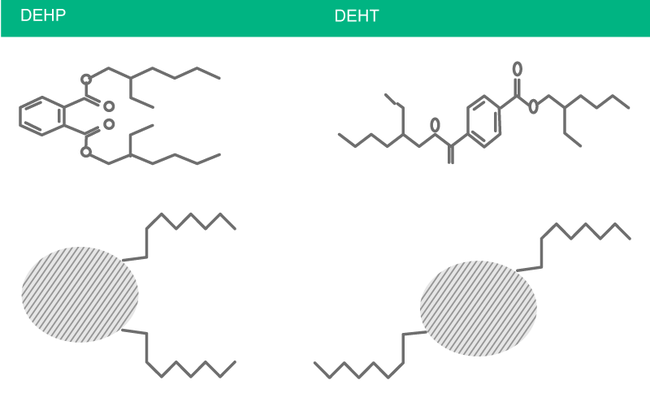

Diethylhexylphthalat (DEHP) ist ein Phthalat – ein Weichmacher, der dazu dient, Medizinprodukte aus PVC (Polyvinylchlorid) flexibler und geschmeidiger zu machen, z. B. Blutbeutel, Leitungen, Katheter und Einmalhandschuhe. Die immer bessere Erforschung der Folgen einer DEHP-Belastung (z. B. Teratogenität, Kanzerogenität oder Beeinträchtigung der Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit) hat zur Entwicklung von alternativen Weichmachern geführt.

Gebräuchliche Nicht-Phthalat-Weichmacher sind TOTM und Hexamoll® DINCH sowie das neu entwickelte DEHT/DOTP (DEHT = Bis(2-ethylhexyl)terephthalat bzw. DOTP = Dioctylterephthalat).

Es wurden bereits viele Weichmacher im Zusammenhang mit PVC eingesetzt. Bei Medizinprodukten ist DEHP der PVC-Weichmacher der Wahl.3

Der Anteil von DEHP in flexiblen Polymermaterialien variiert stark, beträgt jedoch häufig etwa 30 bis 35 % (w/w). Im Gegensatz dazu enthalten Polyethylen und Polypropylen normalerweise keine Weichmacher.4,5

PVC und Weichmacher

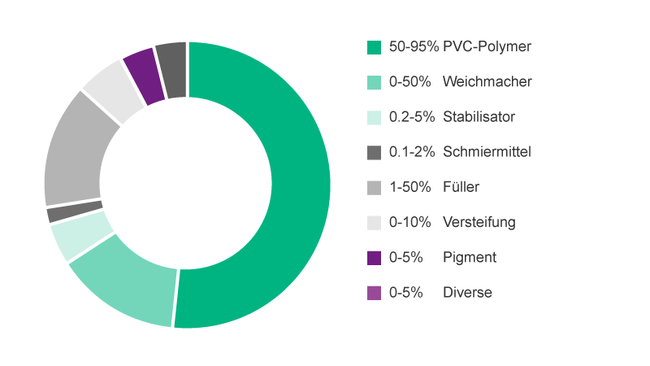

Polyvinylchlorid (PVC) ist ein Kunststoff, der zur Herstellung zahlreicher Alltagsgegenstände verwendet wird, wie z. B. Spielzeug, Baumaterialien wie Bodenbeläge, Kabel und Medizinprodukte.1 Ohne Weichmacher ist PVC bei Raumtemperatur hart und spröde. Demzufolge sind Weichmacher nötig, um dem Polymer eine gewisse Flexibilität zu verleihen. Weichmacher sind Zusatzstoffe, in den meisten Fällen Phthalsäureester, die sich zwischen den Polymerketten einlagern, sie auseinander schieben und somit das Material erheblich weicher machen. Kunststoffe wie PVC werden umso flexibler und strapazierfähiger, je mehr Weichmacher zugefügt werden (s. Abb. 1 zum durchschnittlichen Gehalt an Substanzen in PVC).2

Neben Bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalat (oder auch Diethylhexylphthalat, DEHP) sind die meisten der heutzutage häufig verwendeten Weichmacher Phthalate, und zwar in erster Linie folgende:

- DIDP (Diisodecylphthalat)

- DINP (Diisononylphthalat)

- DBP (Dibutylphthalat)

- BBP (Butylbenzylphthalat)

Neben Phthalaten gibt es auch Nicht-Phthalate, deren aktueller Marktanteil jedoch nur 8 bis 10 % beträgt. Dazu gehören Adipate, Citrate, Phosphate, Trimellitate usw.

DEHP

DEHP kommt in der Natur nicht vor.

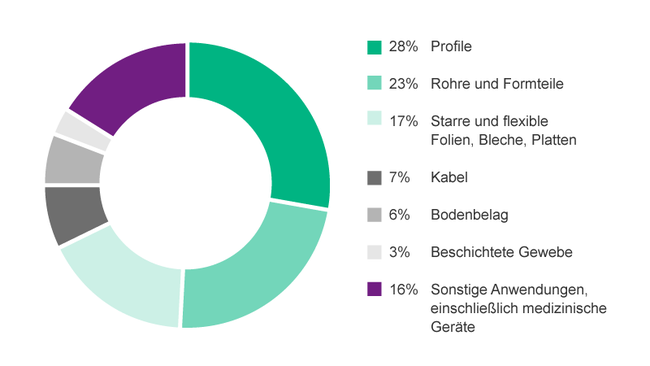

Die weltweite Produktion von DEHP ist in den letzten Jahrzehnten gestiegen. PVC ist nach Polyethylen der am zweithäufigsten verwendete Kunststoff. Weltweit werden derzeit jährlich mehr als 18 Millionen Tonnen produziert. Der chemische Herstellungsprozess von PVC umfasst drei Schritte: die Herstellung des Monomers Vinylchlorid, die Verkettung der Monomereinheiten mittels Polymerisation und schließlich das Beimengen von Zusatzstoffen.6

Die industrielle Verwendung und Endnutzung von DEHP kann im Wesentlichen in drei Produktgruppen unterteilt werden1:

I) PVC

II) Nicht-PVC-Polymere

III) Nicht-Polymere

Ungefähr 97 % des DEHP werden als Weichmacher in Polymeren, hauptsächlich PVC, verwendet.

Einige Beispiele für flexible DEHP-haltige Endprodukte aus PVC sind

- Isolierung von Kabeln und Drähten

- Profile, Schläuche

- Platten, Folien, Wand- und Dachverkleidungen sowie Bodenbeläge

- Beschichtungen und Kunstleder (Autositze, Möbel), Schuhe und Stiefel, Outdoor- und Regenbekleidung

- Kleber für Dichtung und Isolierung und Plastisole, z. B. als Unterbodenschutz von Autos

- Spielzeug und Baby-Artikel (Schnuller, Zahnungsringe, Quietschspielzeug, Nestchen für Babybetten usw.)

- Medizinprodukte

DEHP wird neben anderen Weichmachern als Zusatzstoff für Gummi, Latex, Kitte und Dichtungen, Tinten und Pigmente, Schmierstoffe verwendet.1

Einige Beispiele für DEHP-haltige Nicht-Polymer-Endprodukte sind (Abb. 2):

- Farben und Lacke

- Kleb- und Füllstoffe

- Druckfarben

- Dielektrische Flüssigkeiten in Kondensatoren

- Keramik

PVC und DEHP in Medizinprodukten

Das in Medizinprodukten eingesetzte PVC macht einen sehr geringen Prozentsatz der jährlich hergestellten Gesamtmenge an PVC aus. Dennoch ist die Verwendung von weichmacherhaltigem PVC in einer Vielzahl von Medizinprodukten aus verschiedenen Gründen von großer Bedeutung7:

- Flexibilität unterschiedlich geformter Produkte, von Schläuchen bis hin zu Membranen

- Chemische Stabilität und Sterilisationsfähigkeit

- Geringe Kosten und breite Verfügbarkeit

- Keine Hinweise auf signifikante unerwünschte Folgen für die Patienten

Jährlich werden in Europa ungefähr 3×104 Tonnen7 weichmacherhaltiges PVC für medizinische Anwendungen genutzt. Dazu gehören Infusions- und Blutbeutel sowie Infusionsschläuche, Beutel für die enterale und parenterale Ernährung und Schläuche in Herz-Lungen-Maschinen und Geräten für die extrakorporale Membranoxygenierung.

Wussten Sie schon?

Ursachen

Insbesondere Infusionsbehälter aus DEHP-haltigem PVC sind mit drei wesentlichen Problemen verbunden:

Auswaschen von DEHP

Wir alle sind im Alltag kleinen Mengen DEHP ausgesetzt. Einige Menschen können jedoch durch bestimmte medikamentöse Behandlungen und andere medizinische Maßnahmen hohen Mengen an DEHP ausgesetzt sein. DEHP kann aus dem Kunststoff von Medizinprodukten in Lösungen ausgewaschen werden, die mit dem Kunststoff in Kontakt kommen.

Die ausgewaschene Menge an DEHP ist abhängig von der Temperatur, dem Lipidgehalt der Flüssigkeit und der Dauer des Kontakts mit dem Kunststoff. Bei schwerkranken Patienten sind häufig mehrere dieser Behandlungen oder Maßnahmen erforderlich, wodurch diese Patienten noch höheren Mengen an DEHP ausgesetzt werden.16 Das Material eines typischen Blutbeutels kann 30 bis 40 % DEHP (Gewichtsprozent) enthalten.17 Jaeger und Rubin berichteten über das Auswaschen von DEHP aus PVC-Blutbeuteln in die darin enthaltenen Blutkomponenten.18 Ihren Daten zufolge betrug die Auswaschrate für Vollblut bei einer Lagerungstemperatur von 4°C 0,25 mg DEHP/100 ml/Tag. Für eine Bluttransfusion bei einem Erwachsenen wurde eine DEHP-Belastung von 600 mg beschrieben.19 Das Auswaschen von DEHP aus Blutbeuteln in darin gelagerte Thrombozytenkonzentrate wurde quantitativ bestimmt. Es wurde geschätzt, dass jedem Patienten über 5 Beutel insgesamt 26,4 bis 82,4 mg DEHP zugeführt wurden.19 Für eine Bluttransfusion bei einem Erwachsenen wurde eine DEHP-Belastung von 600 mg beschrieben.20

Da eine Thrombozyteninfusion gewöhnlich 30 min dauert, trägt bei Annahme einer linearen Auswaschrate von DEHP über die Zeit der verwendete Schlauch höchstens 1,0 mg bei. Diese Menge ist zu vernachlässigen.21

Andere beschreiben eine erhebliche Auswaschung von DEHP aus PVC-Beuteln in die darin aufbewahrten Infusionslösungen, die eine parenterale Ernährung22, Zytostatika15 oder Antibiotika enthielten.23,24

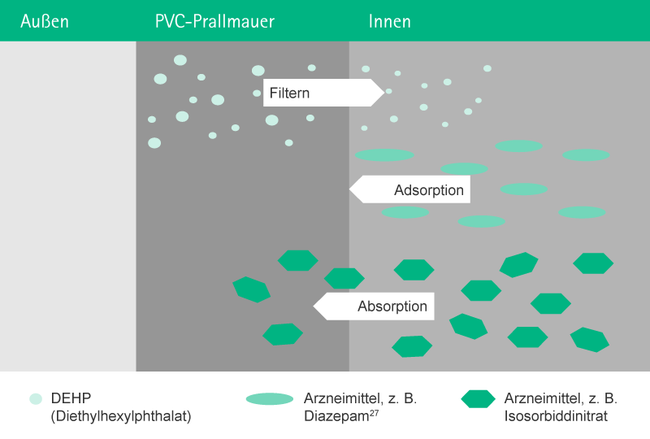

Die Sorption ist ein physikalischer und chemischer Prozess, bei dem sich eine Substanz an eine andere anlagert.

Man unterscheidet wie folgt:

- Auswaschung– Eine Substanz wäscht aus dem Beutelmaterial aus und geht in die Lösung über15

- Adsorption – Ein Wirkstoff einer Lösung, z. B. Diazepam16, haftet innen am Beutelmaterial an

- Absorption – Ein Wirkstoff einer Lösung, z. B. Isosorbiddinitrat, dringt in das Beutelmaterial ein25

Wechselwirkungen von Arzneimitteln in PVC-Beuteln

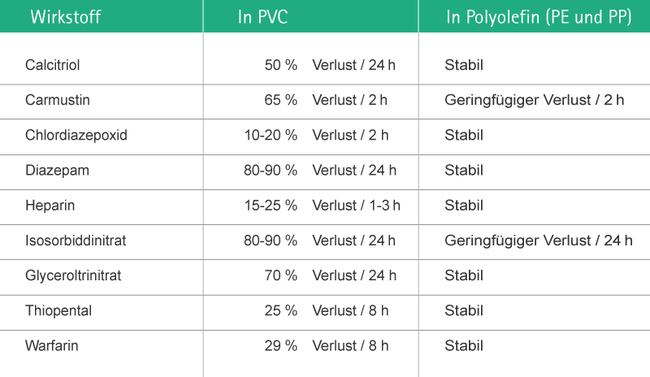

Neben der Menge an DEHP, die aus dem Behälter in die darin enthaltene Lösung ausgewaschen wird, wurde eingehend untersucht, ob die Lösungen in ihrem Behälter stabil sind. Üblicherweise wird die Lagerung in PVC mit der Lagerung in Polyolefinen, d. h. Polyethylen (PE) und Polypropylen (PP), verglichen. Für eine ganze Reihe von Arzneimitteln kann die Lagerung in PVC-Behältnissen nicht empfohlen werden, da sie nicht vollständig stabil sind. Das sind z. B. zytotoxische Wirkstoffe26, Sedativa16,27 und kritische Substanzen wie Glyceroltrinitrat27, Isosorbiddinitrat28, Warfarin-Natrium28 und Thyroxin.29

Umweltexposition

Im Hinblick auf die Umwelt gibt es zwei wichtige Aspekte: Zum einen die Menge an DEHP, die während oder nach der Lebensdauer des Produkts aus dem Kunststoff freigesetzt wird, und zum anderen die Nebenprodukte, die während der Herstellung und der Entsorgung von PVC entstehen.

Freisetzung von DEHP in die Umwelt

Große Mengen an DEHP in Polymeren reichern sich an in:

- Endprodukten mit langer Lebensdauer (z. B. Baumaterialien)

- Deponien

- Müll, der in der Umwelt bleibt (Polymerteile)

- DEHP gilt als schwer abbaubar, solange das Molekül innerhalb der Polymermatrix bleibt. Aus diesem Grund nimmt die Menge an DEHP in der Technosphäre (einschließlich Abfall) weiterhin zu. Die Gesamtverteilung von DEHP beträgt 2 % in der Luft, 21 % im Wasser und 77 % in urbanen/industriellen Böden.1

Nebenprodukte bei der Herstellung und Entsorgung von PVC

Im Zuge der Herstellung und insbesondere der Verbrennung von PVC werden zahlreiche toxische Nebenprodukte in die Umwelt freigesetzt: Polychlorierte Dibenzodioxine (PCDD), polychlorierte Dibenzofurane (PCDF) und dioxinartige polychlorierte Biphenyle (PCB) sind eine Gruppe strukturell verwandter Chemikalien, die in der Umwelt verbleiben und in tierischen Nahrungsquellen und menschlichem Gewebe akkumulieren können.30 Ihre Halbwertzeit im Körper wird auf sieben bis elf Jahre geschätzt.31

Beispiel: Ciprofloxacin

In der amerikanischen Produktinformation zu Cipro® IV (Bayer AG, INN: Ciprofloxacin) wird darauf hingewiesen, dass DEHP aus dem zur Lagerung und Verabreichung verwendeten PVC-Behältnis mit einer Konzentration von 5 ppm (Teile pro Million) auswaschen kann. Zur Abschätzung der Menge an DEHP, die ein Patient durch die Verabreichung von Ciprofloxacin erhält, müssen das Volumen der das Arzneimittel enthaltenden Lösung und die Häufigkeit der Verabreichung bekannt sein. Für leichte Harnwegsinfekte beträgt die empfohlene Dosis Ciprofloxacin 200 mg alle 12 Stunden. Das Arzneimittel wird in einem flexiblen PVC-Behälter mit 200 mg Wirkstoff in 100 ml Lösung vertrieben. Bei einer DEHP-Konzentration in der Lösung von 5 ppm bzw. 5 mg/l betrüge die DEHP-Menge, die ein Patient zusammen mit dem Wirkstoff im Rahmen der Behandlung eines Harnwegsinfekts erhalten würde: 5 mg DEHP/l x 100 ml/Verabreichung x 2 Verabreichungen/Tag x 0,001 l/ml = 1 mg DEHP/Tag. Bei schweren Infektionen ist eine aggressivere Therapie erforderlich. Beispielsweise wird zur Behandlung schwerer Infektionen der Atemwege, Knochen, Gelenke oder der Haut eine Dosis von 400 mg Ciprofloxacin alle 8 Stunden empfohlen. Die Menge an DEHP, die ein Patient bei diesem Regime erhalten würde, betrüge:

5 mg DEHP/L × 200 ml/Verabreichung x 3 Verabreichungen/Tag x 0,001 l/ml = 3 mg DEHP/Tag.

Beispiel: Mischinfusionen mit mehreren Arzneimitteln

Häufig werden mehrere Arzneimittel über dieselbe intravenöse Infusion gleichzeitig infundiert. Ein solcher Fall ist die Parallelinfusion von Chinin und Multivitaminpräparaten. Es wurde gezeigt, dass aus PVC-Beuteln, die nur gelöstes Chinin enthalten, wenig DEHP austritt. Die Gegenwart des lipophilen Multivitamincocktails erhöhte jedoch das Ausmaß der DEHP-Freisetzung aus dem Beutel erheblich. Nach einer Lagerung von Chinin/Multivitamin-Kombinationen über 48 Stunden bei 45°C erreichte die DEHP-Konzentration in den Beuteln 21 mg/ml. Demzufolge würden einem Patienten über die Infusion von 500 ml einer Lösung, die Chinin und einen Multivitamincocktail enthält, 10,8 mg DEHP zugeführt. Für die Verabreichung von Arzneimitteln, die zur Solubilisierung ein lipophiles Vehikel benötigen, sind PVC-freie Beutel erhältlich. Aus PVC-freien Beuteln ist kein Austreten von DEHP zu erwarten. Übereinstimmend mit dieser Erwartung wurde in einer Paclitaxel-Lösung, die für 15 Tage in einem Polyethylen-Behältnis gelagert wurde, kein DEHP nachgewiesen.17

Gesundheitliche Folgen

Gesundheitliche Bedenken in Bezug auf phthalathaltige Weichmacher sind derzeit Gegenstand der Diskussion in den Medien, bei der Gesetzgebung und in wissenschaftlichen Kreisen. Wissenschaft und Industrie arbeiten schon seit langem eng zusammen, um sich mit dieser Problematik auseinanderzusetzen und notwendige Untersuchungen durchzuführen. Deshalb gehören Phthalate heute zu den am besten erforschten und verstandenen chemischen Substanzen.32

Auswirkungen der Auswaschung von DEHP

Negative Auswirkungen von DEHP auf den Menschen

Zahlreiche Studien zeigten, dass die chemische Gruppe der Phthalate und besonders DEHP bei Ratten die Testosteronproduktion in den Hoden beeinträchtigt. Jüngste Untersuchungen lieferten den Beweis, dass DEHP die Testosteronproduktion in den Hoden erwachsener Männer hemmen kann.33

Darüber hinaus wurden unerwünschte Auswirkungen auf das Reproduktionssystem beschrieben, wie beispielsweise eine verminderte Spermienqualität und Anomalien bei der männlichen Genitalentwicklung..34

Im Einklang damit erwiesen sich viele Phthalate in Säugetiermodellen als antiandrogene endokrine Disruptoren.35

Endokrine Disruptoren sind chemische Substanzen, die die hormonelle Signalübertragung verändern können und damit potenziell die Entwicklung von Reproduktions- und Nervensystem, den Stoffwechsel und die Entstehung von Krebs beeinflussen können.35

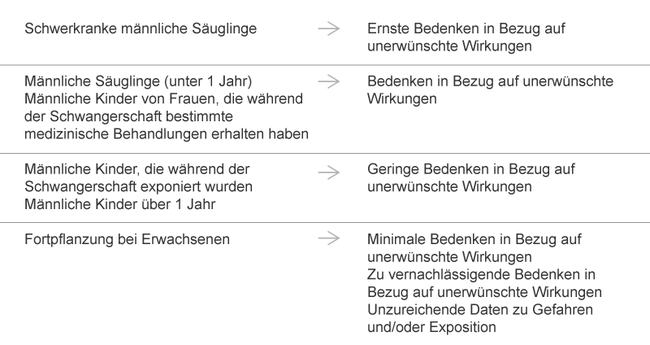

Ernsthafte Bedenken wurden hinsichtlich einer DEHP-Exposition von kranken Neugeborenen und Frühgeborenen geäußert.36 Frühgeborene auf Intensivstationen, die zahlreiche Behandlungen und andere medizinische Eingriffe benötigen, können bezogen auf das Körpergewicht sogar einer höheren DEHP-Exposition ausgesetzt sein als Erwachsene. Diese Exposition kann sogar noch über derjenigen liegen, für die bei Tieren eine Reproduktionstoxizität nachgewiesen wurde.37

Negative Auswirkungen auf den sich entwickelnden Fetus

Tierexperimentelle Studien haben gezeigt, dass sich DEHP besonders negativ auf die fetale Entwicklung auswirkt und unerwünschte Wirkungen im Bereich des reproduktiven Systems hat, wie beispielsweise Veränderungen in den Hoden.33,34

Abb. 7: Schlussfolgerungen des „National Toxicology Program“ zu möglichen negativen Auswirkungen einer DEHP-Exposition auf die Entwicklung und Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit des Menschen.41

Schwangere Frauen, die hohen Phthalatkonzentrationen ausgesetzt sind, haben ggf. ein erhöhtes Risiko, Söhne mit Fehlbildungen der Geschlechtsorgane (Hypospadien und Kryptorchismus), geringer Spermienzahl und erhöhtem Risiko für Hodenkrebs zur Welt zu bringen.34,38

Karzinogenität von DEHP

Für DEHP wurde eine karzinogene Wirkung in der Leber von Ratten und Mäusen beschrieben, deren Induktionswege eingehend untersucht wurden.39 Daneben wurden weitere unerwünschte Wirkungen in Lungen, Herz und Nieren beschrieben.40 Die Internationale Agentur für Krebsforschung (IARC), die Teil der WHO ist, hat DEHP als „möglicherweise karzinogen bei Menschen“ (Gruppe 2b) eingestuft39. Diese Meinung wird von vielen anderen Organisationen, z. B. dem „Department of Health and Human Services“ (Ministerium für Gesundheitspflege und Soziale Dienste) der Vereinigten Staaten, geteilt.41

Im Jahr 2000 wurde DEHP von der IARC heruntergestuft. Dies stieß jedoch auf massive Kritik in der medizinischen und wissenschaftlichen Gemeinschaft, die der IARC vorwarf, wichtige Berichte nicht berücksichtigt zu haben.

Besonders problematisch sind lipophile Substanzen

DEHP diffundiert in lipophile Gewebe und Flüssigkeiten und wird auf diese Weise im Körper verteilt. Dabei macht es keinen Unterschied, ob die Aufnahme oral, parenteral, inhalativ oder über die Haut erfolgt. Daher raten viele Autoren zur Verwendung von Behältern aus Polyethylen oder Polypropylen anstelle von PVC15, und immer mehr pharmazeutische Hersteller schließen bei ihren Präparaten die Verwendung von PVC-Beuteln aus. Beispiele hierfür sind Paclitaxel und Temsirolimus.

Thrombogenität von DEHP

PVC-Materialien sind für ihre Thrombogenität bekannt, und es gibt deutliche Hinweise darauf, dass das Ausmaß der Thrombozytenaggregation auf die Anwesenheit von DEHP im Material und nicht auf das PVC selbst zurückzuführen ist. Darüber hinaus fällt die Komplementaktivierung, ein Vorgang, der mit unerwünschten hämatologischen Wirkungen verbunden ist, nach Kontakt von Blut mit DEHP-haltigem PVC stärker aus als nach Kontakt mit anderen Polymeren. Alle diese Faktoren können beim Patienten unerwünschte klinische Folgen haben.43,44

Peritonealsklerose im Zusammenhang mit DEHP-Exposition

Die Peritonealsklerose ist eine schwerwiegende Komplikation einer Peritonealdialyse. Neben anderen Faktoren scheint auch DEHP bei der Pathogenese dieser Erkrankung eine Rolle zu spielen. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen weisen darauf hin, dass die DEHP-Konzentrationen in Dialysaten, die in DEHP-haltigen Beuteln gelagert werden, ausreichend hoch sind, um den Prozess der Peritonealsklerose zu initiieren und eine Sklerose zu verursachen.

Die klinische Relevanz der Peritonealsklerose ist nicht zu unterschätzen, da Patienten mit verminderter dialytischer Kapazität des Peritoneums auf eine Hämodialyse umgestellt werden müssen.17

Auswirkungen der Sorption von PVC

Sorption von Wirkstoffen an/durch PVC und Konsequenzen für die Therapie

Während es bei der Diskussion um das Auswaschen von Weichmachern vor allem um die toxikologischen Eigenschaften von Arzneimittelverpackungssystemen geht, beeinflusst die Sorption (Sammelbezeichnung für Absorption und Adsorption) von Bestandteilen einer Arzneimittelformulierung die Dosierung des Wirkstoffs und hat eine verminderte Wirkstoffzufuhr zum Patienten zur Folge. Damit hat die Sorption Einfluss auf Wirksamkeit und Erfolg der Therapie.27

Abb. 6 enthält eine Auflistung von Wirkstoffen, die nicht mit PVC kompatibel sind. Die beispielhaft ausgewählten Wirkstoffe und ihre Anwendungsbereiche machen deutlich, dass die Gefahr einer erheblichen Unterdosierung der Substanzen mit den entsprechenden Konsequenzen besteht:

- Eine Unterdosierung von Carmustin, einem bei Glioblastomen (bösartiger Hirntumor) eingesetzten Chemotherapeutikum, kann zur Unwirksamkeit der Behandlung und damit zum Fortschreiten der Krebserkrankung führen.

- Eine Unterdosierung von Heparin oder Warfarin, zweier gerinnungshemmender Wirkstoffe, kann zu Blutgerinnseln und/oder zu einer Lungenembolie führen.

- Eine Unterdosierung von Thiopental, einem schnell und kurz wirksamen Allgemeinanästhetikum aus der Gruppe der Barbiturate, kann zu unbeabsichtigtem Bewusstsein des Patienten beispielweise während einer Operation führen.

- Eine Unterdosierung von Isosorbiddinitrat und Glyceroltrinitrat, zweier gefäßerweiternder Wirkstoffe, die bei Angina pectoris zum Einsatz kommen, könnte die Substanzen wirkungslos machen und das Fortschreiten der Angina zu einem Herzinfarkt zur Folge haben.

- Chlordiazepoxid und Diazepam, zwei Sedativa und Anxiolytika, sind unter Umständen nicht so effektiv wie gewünscht.

Wenn der Effekt der Sorption dem Anwender bekannt ist und dieser deshalb die verabreichte Wirkstoffdosis erhöht, bedeutet das erhebliche zusätzliche Kosten für den Dienstleister und die Kostenträger, die vermeidbar wären.

Folgen der Umweltexposition

Freisetzung von DEHP in die Umwelt hat die gleichen Auswirkungen, wie sie oben für andere Substanzen beschrieben wurden: Durch Anreicherung in der Nahrungskette gelangt die Substanz in den menschlichen Körper. Mögliche Folgen sind endokrine Disruption, Krebs sowie verschiedene Fehlbildungen und Erkrankungen.

Dioxine und Furane, die im Zuge der Herstellung und Verbrennung von PVC in die Umwelt freigesetzt werden, haben nachweisliche toxische Wirkungen. Dazu gehören dermale Toxizität, Störungen der Entwicklung des Nervensystems, Immuntoxizität, Auswirkungen auf die Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit, Teratogenität, endokrine Disruption, metabolisches Syndrom und Karzinogenität.30

1997 stufte die Internationale Agentur für Krebsforschung TCDD (2,3,7,8-Tetrachlordibenzo-p-dioxin), die giftigste Verbindung der Gruppe, als Gruppe-I-Karzinogen ein (ausreichende Beweise für Karzinogenität),45 und eine aktuelle Übersichtsarbeit zu bekannten und neueren Daten unterstützt diese Entscheidung.46

Wie bereits unter „Ursachen“ beschrieben, nimmt die aus Baumaterialien, Abfall und Deponien stammende Menge an DEHP in Luft, Boden und Wasser kontinuierlich zu. Diese Umweltexposition addiert sich zu der Exposition durch Lebensmittel, Medizinprodukte und andere Produkte hinzu und damit erhöhen sich auch die beschriebenen Risiken.

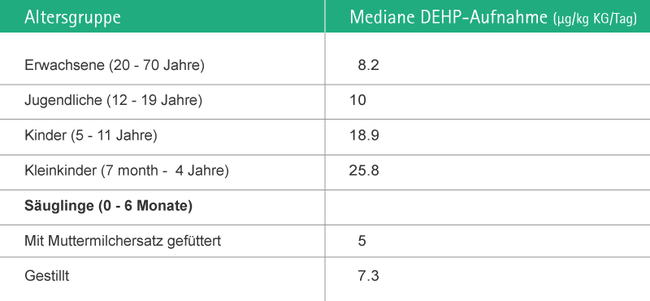

Die Dioxine und Furane, toxische Nebenprodukte, die bei der Herstellung und Entsorgung von PVC freigesetzt werden (z. B. PCDDs, PCDFs und PCBs), sind durch sehr lange Halbwertzeiten gekennzeichnet. Ihre Konzentration steigt im Verlauf der Nahrungskette von Stufe zu Stufe weiter an, und zwar insbesondere im Fettgewebe. Abb. 8 zeigt die mediane DEHP-Aufnahme beim Menschen nach Altersgruppen.

Dioxine und Furane gehören zu den giftigsten bekannten Chemikalien. Die kurzzeitige Exposition gegenüber hohen Dioxinmengen kann beim Menschen zu Hautläsionen wie einer Chlorakne und fleckiger Dunkelfärbung der Haut sowie zu einer Beeinträchtigung der Leberfunktion führen. Eine Langzeitexposition hat eine Beeinträchtigung des Immunsystems, des sich entwickelnden Nervensystems, des endokrinen Systems und der reproduktiven Funktion zur Folge.

Bei Tieren verursachte die chronische Exposition gegenüber Dioxinen verschiedene Krebsformen. Im Jahr 1997 untersuchte die zur WHO gehörige Internationale Agentur für Krebsforschung (International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC) TCDD (2,3,7,8-Tetrachlordibenzo-p-dioxin).47 Auf Grundlage der Daten aus tierexperimentellen Studien und epidemiologischen Daten vom Menschen stufte die IARC TCDD als „karzinogen bei Menschen“ ein.

Die gesundheitlichen Folgen der Exposition gegenüber Dioxinen und Furanen sind in epidemiologischen und toxikologischen Studien umfassend dokumentiert.48 Darüber hinaus sind aus Unfällen wie dem schweren Unglück im italienischen Seveso aus dem Jahr 1976 verschiedene ernsthafte Folgen bekannt. Damals wurde eine Wolke giftiger Chemikalien, darunter auch 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlordibenzo-p-dioxin oder TCDD, in die Luft freigesetzt und kontaminierte ein Gebiet von 15 Quadratkilometern, in dem 37.000 Menschen lebten.

Die Exposition von Menschen und insbesondere von in der Entwicklung befindlichen Kindern gegenüber DEHP kann, wie gezeigt wurde, erhebliche gesundheitliche Beeinträchtigungen hervorrufen. Diese können wiederum bedeutende ökonomische Konsequenzen haben, insbesondere bei schwereren Erkrankungen, die eine hohe ökonomische Belastung bedeuten.

Präventionsstrategien

Wie auf den vorhergehenden Seiten beschrieben, besteht Einigkeit darüber, dass die Verwendung von DEHP als Weichmacher bedenklich ist. Wissenschaftliche Gremien auf der ganzen Welt empfehlen die Beschränkung seines Einsatzes.1,4,7,17,49,50 Darüber hinaus gibt es heute zahlreiche Alternativen, wie die Verwendung anderer Weichmacher in PVC oder die Verwendung völlig anderer, PVC-freier Materialien. Dies war Anlass für zahlreiche internationale, nationale und regionale Aktivitäten, zum Teil mit gesetzgeberischen Maßnahmen im Gesundheitswesen sowie in vielen anderen Branchen, wie der Spielzeug-, Nahrungsmittel- und Getränkeindustrie.

Gesetze und Richtlinien

- Lebensmittel-Verpackungen aus PVC (mit oder ohne DEHP) wurden in zahlreichen Ländern, darunter Kanada, Spanien, Südkorea und Tschechien, entweder verboten oder beschränkt.57

- In der Verordnung 143/2011/EU wird Bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalat (DEHP) als reproduktionstoxisch eingestuft. Ab dem 21. Januar 2015 ist die Vermarktung und Verwendung von DEHP ohne Sondergenehmigung verboten.53

- Im Januar 2010 gab der australische Handelsminister Craig Emerson aufgrund der Auswirkungen auf die Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit ein Verbot für Artikel mit mehr als 1 % DEHP bekannt.56

- Im August 2008 trat in den USA die vom Kongress unterzeichnete „Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act“ (CPSIA, etwa „Gesetz zur Verbesserung der Sicherheit von Konsumartikeln“) in Kraft, die in Abschnitt 108 festlegt, dass mit Wirkung vom 10. Februar 2009 die Herstellung für den Verkauf, das Anbieten zum Verkauf, der kommerzielle Vertrieb und der Import von Kinderspielzeug und Baby-Artikeln, die DEHP, DBP oder BBP in Konzentrationen von mehr als 0,1 % enthalten, gesetzlich verboten sind.

- Die Verordnung 1907/2006/EG des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates zur Registrierung, Bewertung, Zulassung und Beschränkung chemischer Stoffe (REACH) ist am 1. Juni 2007 in Kraft getreten. In dieser Verordnung wird DEHP als besonders besorgniserregender Stoff eingestuft. Derartige Stoffe müssen durch die Europäische Chemikalienagentur (ECHA) in Helsinki zugelassen werden.54

- Gemäß Richtlinie 2007/47/EG müssen DEHP-haltige Medizinprodukte entsprechend gekennzeichnet sein.55

- Bei der Verpackung von Lebensmitteln wurde der Einsatz von DEHP in Materialien mit Kontakt zu Lebensmitteln bereits durch Richtlinie 2007/19/EG der Kommission vom 30. März 2007 über Materialien und Gegenstände aus Kunststoff, die dazu bestimmt sind, mit Lebensmitteln in Berührung zu kommen, und Richtlinie 85/572/EWG des Rates über die Liste der Simulanzlösemittel für die Migrationsuntersuchungen von Materialien und Gegenständen aus Kunststoff, die dazu bestimmt sind, mit Lebensmitteln in Berührung zu kommen, beschränkt.

- Das wissenschaftliche Expertengremium zu DEHP der kanadischen Gesundheitsbehörde „Health Canada“ empfahl unter anderem, dass Aufbewahrungsbehälter für die Verabreichung von lipophilen Arzneimitteln kein DEHP enthalten sollten.23 Darüber hinaus hat Health Canada vorgeschlagen, den Verkauf, die Bewerbung und den Import von DEHP-haltigem Spielzeug, sowie von DEHP-haltigen Produkten, die wahrscheinlich in den Mund genommen werden, für Kinder unter drei Jahren zu verbieten.59

- Das Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM) empfiehlt bei Frühgeborenen und Neugeborenen die Verwendung von alternativen Produkten anstelle von Medizinprodukten aus DEHP-haltigem PVC. Das BfArM mahnt außerdem Hersteller von Medizinprodukten, DEHP-haltige Produkte zu kennzeichnen und sich mehr um die Entwicklung sichererer Alternativen zu bemühen.58

- Gemäß Richtlinie 2004/93/EG der Kommission vom 21. September 2004 zur Anpassung der Richtlinie 76/768/EWG des Rates in Bezug auf kosmetische Mittel sollen DEHP-haltige Kosmetikprodukte seit dem 1. April 2005 nicht mehr an Verbraucher in der EU geliefert werden.

- Argentinien, Dänemark, Deutschland, Fidschi, Finnland, Griechenland, Italien, Japan, Mexiko, Norwegen, Österreich, Schweden, Tschechien und Zypern haben den Einsatz von Phthalaten in Kinderspielzeug beschränkt.52

- Die Kampagne „Health Care Without Harm“ ist ein internationales Bündnis von 420 Organisationen in 51 Ländern. Zu den Organisationen gehören Krankenhäuser und Gesundheitssysteme, Mitglieder medizinischer Berufsgruppen, Gemeinschaften, Interessengemeinschaften, Gewerkschaften, Umwelt- und Gesundheitsorganisationen sowie religiöse Gruppen. Zu den Zielen der Kampagne gehört es, die Verwendung von PVC und langlebigen giftigen Chemikalien schrittweise zu reduzieren und den Impuls für eine breiter angelegte Kampagne für ein schrittweises Verbot von PVC zu geben.64

- In ihrem neuesten Entwurf der Richtlinie 2002/95/EG (RoHS) zur Beschränkung der Verwendung bestimmter gefährlicher Stoffe in Elektro- und Elektronikgeräten hat die Europäische Union DEHP in die Liste der verbotenen Substanzen aufgenommen.

- Die Europäische Union empfiehlt für Medizinprodukte den Einsatz anderer Materialien anstelle von DEHP-PVC.51

- Bedenken in Bezug auf die Freisetzung von Dioxinen durch Müllverbrennung veranlassten die japanische Regierung dazu, ein neues Gesetz zu Behältern und Verpackungsmaterial zu erlassen, das die Hersteller dieser Produkte dazu verpflichtete, Abfallprodukte ab dem Jahr 2000 zu recyceln. Das Gesetz veranlasste mehrere große japanische Hersteller von Haushaltsartikeln und Kosmetika dazu, Zeitpläne zu veröffentlichen, die anzeigten, bis wann sie bei verschieden Arten von Verpackungen für Kosmetika, Lebensmittel und Pharmazeutika auf Polypropylen und andere Materialien umsteigen würden.61

- Auch die US-amerikanische Food and Drug Administration hat ein „FDA Safety Assessment“ (Sicherheitsbewertung) und eine „Public Health Notification“ (Bekanntmachung zur öffentlichen Gesundheit) herausgegeben, in denen sie Gesundheitsdienstleister mahnt, bei bestimmten gefährdeten Patienten Alternativen zu DEHP-haltigen Produkten zu verwenden.17

- Gemäß den Anforderungen der Stockholmer Konvention über die Freisetzung von Dioxinen und anderen langlebigen organischen Schadstoffen (Furane, Hexachlorbenzen und PCB) soll jede Vertragspartei zumindest die auf anthropogene Quellen zurückzuführende Gesamtfreisetzung jeder der ... chemischen Verbindungen verringern, mit dem Ziel der kontinuierlichen Verringerung und - sofern durchführbar - der vollständigen Elimination.60

Initiativen und Kampagnen

- Im November 2011 gab die Food and Drug Administration (FDA) einen neuen erlaubten Höchstwert (0,006 mg/l) für Diethylhexylphthalat (DEHP) in abgefülltem Wasser bekannt. Die Hersteller sind verpflichtet, die Konzentrationen zu kontrollieren.62

- Der US-amerikanische Managed-Healthcare-Provider Kaiser Permanente sagte aus, dass er keine aus PVC hergestellten oder den Weichmacher enthaltenden Infusionsbeutel mehr kaufen wird. Dies ist Teil der ständigen Bemühungen des Unternehmens, den 8,9 Millionen Menschen, die in seinen Krankenhäusern, Arztpraxen und Gesundheitseinrichtungen versorgt werden, einen besseren Gesundheitsschutz und mehr Sicherheit zu bieten.63

- Die OSPAR-Liste der vorrangig zu behandelnden Chemikalien enthält mehrere Substanzen, die Nebenprodukte der Herstellung von Chlor und PVC oder Zusatzstoffe von PVC sind: Dioxine und Furane, Chlorparaffine, Quecksilber und organische Quecksilberverbindungen, Blei und organische Bleiverbindungen, organische Zinnverbindungen, bestimmte Phthalate (DBP und DEHP).66

- In den USA eliminieren Kaiser Permanente sowie das Miller Children‘s Hospital in Long Beach, das Lucile Packard Children‘s Hospital an der Stanford University und das John Muir Medical Center in Walnut Creek (alle Kalifornien) PVC-haltige Medizinprodukte derzeit allmählich aus ihren Neugeborenen-Intensivstationen.64

- Der Bund für Umwelt- und Naturschutz Deutschland (BUND), das Bündnis „Health Care Without Harm“ (HCWH) und die Europäische Akademie für Umweltmedizin (EUROPAEM) haben die Initiative „Schadstofffreies Krankenhaus“ ins Leben gerufen. Die Umweltorganisationen haben die Krankenhäuser in Deutschland dazu aufgerufen, auf PVC-haltige Medizinprodukte zu verzichten.65 Die Kinderklinik Glanzing des Wiener Krankenanstaltenverbunds ist weltweit die erste Neonatalstation, die angekündigt hat, vollkommen ohne PVC-Kunststoffe auszukommen.64

- In Spanien haben mehr als 60 Kommunalverwaltungen Maßnahmen zur allmählichen Eliminierung von PVC beschlossen. Dasselbe gilt für Deutschland, wo immer mehr Städte erklären, in öffentlichen Gebäuden auf PVC zu verzichten.52

Forschung in der Industrie

Abb. 10: DEHT steht für Bis(2-ethylhexyl)terephthalat, auch DOTP (Dioctylterephthalat) genannt. Seine chemische Struktur unterscheidet sich von DEHP.

- B. Braun hat Bis(2-ethylhexyl)terephthalat [auch Dioctylterephthalat genannt (Abkürzung: DEHT bzw. DOTP)], einen phthalatfreien Weichmacher mit abweichender chemischer Struktur, erworben und weiter entwickelt. DEHT bzw. DOTP ist der einzige bekannte Weichmacher für flexibles PVC, der in Untersuchungen keine toxischen Nebenwirkungen verursacht (siehe Abb. 10).7, 67

- Immer mehr Chemieproduzenten entwickeln und produzieren alternative Weichmacher. Für die Zulassung dieser Weichmacher, wie z. B. TOTM/TEHTM und Hexamoll® DINCH sind umfangreiche und gründliche Untersuchungen notwendig.

- Zahlreiche Hersteller von Medizinprodukten, unter ihnen B. Braun, haben in die Erforschung alternativer Materialien zu DEHP-PVC zur Verwendung in Medizinprodukten investiert.

Eigenschaften des alternativen Weichmachers DEHT

Bis(2-ethylhexyl)terephthalat (DEHT) ist ein phthalatfreier Allzweckweichmacher und seit 1975 im Handel. Coca Cola und andere Unternehmen verwenden DEHT seitdem für ihre Flaschen. Das „T“ in PET steht für Terephthalat. Auch die Spielzeugindustrie verwendet diesen Weichmacher auf vielfache Weise.

DEHT wurde von der Eastman Company entwickelt und produziert. Daher lautet einer seiner Handelsnamen Eastman 168.

Toxizitätsprofil von DEHT

Das Toxizitätsprofil von DEHT wurde in zahlreichen In-vitro- und In-vivo-Studien untersucht. In Studien zur akuten Toxizität nach oraler, dermaler oder okularer Exposition bzw. nach Inhalation lag der Fokus auf der akuten, subakuten und subchronischen Toxizität. Alle Studien zeigten ein ausgezeichnetes toxikologisches Profil.

Untersuchungen zur Entwicklungstoxizität ergaben bei männlichen Ratten weder eine Veränderung der Geschlechtsdifferenzierung während der Entwicklung noch eine Wirkung auf die Entwicklung der männlichen Geschlechtsorgane. Ebenso wurden keine östrogenen Wirkungen beobachtet. Sämtliche Tests auf Genotoxizität und Mutagenität fielen negativ aus. Es wurde kein Einfluss auf die Tumorinzidenz und Tumorigenität und keine Induktion von Leberperoxisomen festgestellt. Letzteres gilt als Hinweis auf eine potenzielle Tumorigenität.

In einer GLP-konformen Toxizitätsstudie, in der Ratten 4 Wochen lang DEHT als Dauerinfusion erhielten, wurde intravenös infundiertes DEHT in einer Dosis von bis zu einschließlich 381,6 mg/kg/Tag systemisch und lokal ohne Auftreten unerwünschter Wirkungen vertragen (NOAEL=381,6 mg/kg x Tag). Insbesondere traten keine Wirkungen auf Fortpflanzungsgewebe/-organe, Nieren, Hepatozyten und Leberperoxisomen - bekannte Zielstrukturen der DEHP-Toxizität - auf. In einer klinischen Studie mit 203 gesunden Probanden wurde untersucht, inwieweit DEHT Hautreizungen verursacht.68 DEHT erwies sich als nicht hautreizend und löste keine Kontaktsensibilisierung aus.

Diese Daten zeigen, dass der Weichmacher DEHT (Eastman 168) beim Menschen eine geringe akute Toxizität besitzt, im Wesentlichen nicht hautreizend ist und mit einem geringen Risiko für eine Kontaktsensibilisierung verbunden ist.69

Zulassungsprofil von DEHT

DEHT-Eastman-168 wurde weltweit von verschiedenen Behörden eingehend bewertet und in Listen zugelassener Stoffe aufgenommen.

USA: gemäß Food Contact Notification (FCN) für zahlreiche Anwendungen mit Kontakt zu Lebensmitteln anerkannt.70

Europäische Union: Zulassung durch die Europäische Behörde für Lebensmittelsicherheit (EFSA); Bewertung durch SCENIHR für den Einsatz in medizinischen Anwendungen. DEHT ist gemäß REACH kein CMR-Stoff (also nicht krebserzeugend, nicht mutagen [erbgutverändernd] und nicht reproduktionstoxisch [fortpflanzungsgefährdend]).54

Produkte, die kein DEHP enthalten, können durch geeignete Symbole als DEHP-frei gekennzeichnet werden.

Deutschland: vom Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR) für die Verwendung in weichmacherhaltigem PVC in Getränkeschläuchen, Deckelauskleidungen und Lebensmittelverpackungen zugelassen.

Schweiz: DEHT steht nicht auf der Schweizer Giftliste und gilt demnach nicht als toxisch.

Die japanische Hygienic PVC Association führt DEHT auf ihrer Positivliste.

Umweltprofil

DEHT ist nur sehr schlecht in Wasser löslich. In destilliertem Wasser wird seine Löslichkeit mit 0,4 μg/l angegeben. Den Daten zur aquatischen Toxizität zufolge gab es bei keiner der untersuchten Spezies in Konzentrationen an oder nahe der Wasserlöslichkeitsgrenze des Materials akute oder chronische Wirkungen. Eine Studie zeigte außerdem bei Konzentrationen in Höhe des Mehrfachen der Löslichkeitsgrenze unter den Testbedingungen keine Auswirkungen auf das Überleben. In keiner der Studien wurden unter den getesteten Konzentrationen subletale Wirkungen wie beispielsweise solche auf das Wachstum, die Reproduktion, die Schalenzusammensetzung oder die Schlupffähigkeit von Eiern festgestellt. Da DEHT in aquatischem Milieu tendenziell stark an Sedimente sorbieren würde, wurde eine Sediment-Wasser-Toxizitätsstudie mit dotiertem Sediment an Chironomiden gemäß OECD durchgeführt, um zu zeigen, dass DEHT keine negativen Auswirkungen auf aquatische Sedimentlebewesen hat. In dem Sedimenttest lag die EC50 höher als die höchste für die Methode empfohlene Testkonzentration.

Untersuchungen zum biologischen Abbau zeigten, dass innerhalb von 28 Tagen 37 - 56 % der ursprünglichen DEHT-Menge abgebaut werden.

Diese Studien zeigen auch, dass DEHT sowohl einem Primärabbau als auch einem Endabbau unterliegt.69

Weitere Materialien für Medizinprodukte und Arzneimittelbehälter

Vor dem Hintergrund der Defizite von PVC, insbesondere der Sorptionseffekte, die Einfluss auf Wirksamkeit und Erfolg der Therapie haben, werden weitere Materialien für Medizinprodukte und Arzneimittelbehälter untersucht. Stärker inerte Polymere wie Polyethylenterephthalat (PET) und Polyamid (PA) zeigen weniger Wechselwirkungen.71,72 Andererseits ist nicht jedes Polymer als Verpackungsmaterial für Pharmazeutika geeignet. Aufgrund seiner Steifigkeit kann PET beispielsweise kaum für flexible Schläuche oder Beutel eingesetzt werden.27

Solche Überlegungen haben außerdem zur Entwicklung von Verbundmaterialien wie Mehrschichtfolien geführt. Bei ihnen besteht die innere Schicht aus Polypropylen und äußere Schichten aus Polyethylen und Polyester.

Sorptionsverhalten von Polyethylen/Polypropylen

Polyethylen (PE) und Polypropylen (PP), zwei Vertreter der Klasse der Polyolefine, sind zwei Beispiele für Materialien, die nachweislich für die Herstellung von Infusionsbehältern geeignet sind. Gemäß Europäischem Arzneibuch73 sind Arzneimittelbehälter aus medizinischem PE frei von Weichmachern, Zusatzstoffen und anderen Substanzen, die potenziell in das Endpräparat migrieren können. Sie sind chemisch inert und toxikologisch unbedenklich.

Als repräsentative Vertreter der bekannten Gruppe von Wirkstoffen, die eine erhebliche Sorption an PVC aufweisen, wurden Glyceroltrinitrat (Nitroglycerin) und Diazepam hinsichtlich ihres Sorptionsverhaltens an/durch alternative Kunststoffe untersucht. Beide Wirkstoffe zeigten bei PE und PP eine signifikant geringere Sorption als bei Standardschläuchen aus PVC.27

Mehrere andere Studien wiesen ebenfalls nach, dass PE/PP im Vergleich zu anderen Kunststoffen das geringste Sorptionspotenzial für Wirkstoffe bieten.74,75,76

Allgemein zeigte eine Modellierung der Eigenschaften von in pharmazeutischen Behältersystemen eingesetzten Kunststoffen, mit darin enthaltenen Lösungen in Wechselwirkung zu treten, dass PP die niedrigste Bindungsneigung für Arzneimittel besitzt, dicht gefolgt von PE.77

Umweltwirkungen von Polyethylen/Polypropylen

Heutzutage wird der Großteil des medizinischen Abfalls verbrannt. So schreibt beispielsweise im Vereinigten Königreich die „Landfill Directive“ vor, dass Klinikabfall nicht auf Deponien entsorgt werden darf, sondern verbrannt werden muss. Wie bereits erläutert, entstehen bei der Verbrennung von PVC polychlorierte Dibenzodioxine und Dibenzofurane (PCDD/PCDF), die beide sowohl im Rauchgas als auch in der Asche enthalten sind und in die Umwelt freigesetzt werden.

Wie alle Kohlenwasserstoffe brennen Polyethylen und Polypropylen sehr gut. Bei vollständiger Verbrennung bleiben als Verbrennungsprodukte lediglich Kohlendioxid und Wasser übrig, die beide nicht toxisch sind und kein Umweltrisiko darstellen.78

Produktempfehlung zur Risikoprävention

Literaturangaben

1 European Union Risk Assessment Report. bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP)

2 Cadogan DF, Howick CJ (2000)

Plasticizers in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry,

Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi: 10.1002/14356007.a20_439.

3 Safety Assessment of Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) Released from PVC Medical Devices

http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM080457.pdf

4 Umweltbundesamt, Berlin, Hrsg. (2/2007)

Phthalate – die nützlichen Weichmacher mit den unerwünschten Eigenschaften: 3, 10.

5 Kroschwitz JI (1998)

Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology.

Fourth Edition. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

6 http://www.chm.bris.ac.uk/webprojects2001/esser/manufacture.html

7 SCENIHR opinion on the safety of medical devices containing dehp plasticized pvc or other plasticizers on neonates and other groups possibly at risk 2008.

8 Haishima Y, Seshimo F, Higuchi T, Yamazaki H, Hasegawa C, et al. (2005)

Development of a simple method for predicting the levels of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate migrated from PVC medical devices into pharmaceutical solutions.

Int J Pharm 2005; 298:126-42.

9 Hanawa T, Muramatsu E, Asakawa K, Suzuki M, Tanaka M, et al. (2000)

Investigation of the release behavior of diethylhexyl phthalate from the polyvinyl-chloride tubing for intravenous administration.

Int J Pharm; 210:109-15.

10 Hanawa T, Endoh N, Kazuno F, Suzuki M, Kobayashi D, et al. (2003)

Investigation of the release behavior of diethylhexyl phthalate from polyvinyl chloride tubing for intravenous administration based on HCO60.

Int J Pharm; 267:141-9.

11 Loff S, Kabs F, Witt K, Sartoris J, Mandl B, Niessen KH, Waag KL (2000)

Polyvinylchloride infusion lines expose infants to large amounts of toxic plasticizers.

J Pediatr Surg; 35:1775-81.

12 Loff S, Kabs F, Subotic U, Schaible T, Reinecke F, Langbein M (2002)

Kinetics of diethylhexylphthalate extraction from polyvinylchloride-infusion lines.

JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr; 26:305-9.

13 Loff S, Subotic U, Reinicke F, Wischmann H, Brade J (2004)

Extraction of Di-ethylhexyl-phthalate from Perfusion Lines of Various Material, Length and Brand by Lipid Emulsions.

J Pediatr Gastroenteral Nutr; 39:341-345.

14 Bourdeaux D, Sautou-Miranda V, Bagel-Boithias S, Boyer A, Chopineau J (2004)

Analysis by liquid chromatography and infrared spectrometry of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate released by multilayer infusion tubing.

J Pharm Biomed Anal; 35:57-64.

15 de Lemos ML, Hamata L, Vu T. (2005)

Leaching of diethylhexyl phthalate from polyvinyl chloride materials into etoposide intravenous solutions.

J Oncol Pharm Pract;11(4):155-7

16 Trissel LA, Pearson SD (2/1994)

Storage of lorazepam in three injectable solutions in polyvinyl chloride and polyolefin bags.

Am J Hosp Pharm; 1;51(3):368-72.

17 FDA Public Health Notification: PVC Devices Containing the Plasticizer DEHP.

18 Rubin RJ, Schiffer CA (1976)

Fate in humans of the plasticizer, di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate, arising from transfusion of platelets stored in vinyl plastic bags.

Transfusion; 16(4): 330–335.

19 Jaeger RJ, Rubin RJ (1972)

Migration of a phthalate ester plasticizer from polyvinyl chloride blood bags into stored human blood and its localization in human tissues.

N Engl J Med; 287(22): 1114–1118.

20 Sjöberg P, Bondesson U, Sedin G and Gustafsson J (1985)

Disposition of di- and mono- 2ethylhexyl)phthalate in newborn infants subjected to exchange transfusions.

Eu J Clin. Invest; 15: 430-436.

21 Easterling RE, Johnson E, Napier EA (1974)

Plasma extraction of plasticizers from “medical grade” polyvinylchloride tubing.

Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 147: 572–574.

22 Bagel S, Dessaigne B, Bourdeaux D, Boyer A, Bouteloup C, Bazin JE, Chopineau J, Sautou V. (2011)

Influence of lipid type on bis (2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) leaching from infusion line sets in parenteral nutrition.

JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr; 35(6): 770-5

23 Health Canada (2002) An exposure and toxicity assessment. Medical Devices Bureau, Therapeutic Products Directorate, Health Products and Food Branch, Ottawa, Canada.

24 Pearson SD, Trissel LA (1993)

Leaching of diethylhexyl phthalate from polyvinyl chloride containers by selected drugs and formulation components.

Am J Hosp Pharm; 50:1405-9.

25 Lee MG, Fenton-May V (1981)

Absorption of isosorbide dinitrate by PVC infusion bags and aministration sets.

J Clin Hosp Pharm; Sep;6 (3):209-11.

26 Beitz C, Bertsch T, Hannak D, Schrammel W, Einberger C, Wehling M (8/2005)

Compatibility of plastics with cytotoxic drug solutions—comparison of polyethylene with other container materials.

Int Journ of Pharm; (1)185: 113–121.

27 Treleano A, Wolz G, Brandsch R, Welle F (3/2009)

Investigation into the sorption of nitroglycerin and diazepam into PVC tubes and alternative tube materials during application.

Int J Pharm; 18; 369(1-2):30-7.

28 Martens HJ, De Goede PN, Van Loenen AC (2/1990)

Sorption of various drugs in polyvinyl chloride, glass, and polyethylene-lined infusion containers.

Am J Hosp Pharm; 1990 Feb;47(2):369-73.

29 Frenette AJ, MacLean RD, Williamson D, Marsolais P, Donnelly RF (9/2011)

Stability of levothyroxine injection in glass, polyvinyl chloride, and polyolefin containers.

Am J Health Syst Pharm; 15;68(18):1723-8.

30 Hedley AJ, Wong TW, Hui LL, Malisch R, Nelson EA (2/2006)

Breast milk dioxins in Hong Kong and Pearl River Delta.

Environ Health Perspect; 114(2):202-8.

31 WHO Factsheet no 225, 2010,

Dioxins and their effect on human health, May 2012

32 http://www.pvc.org/en/p/Health_concerns_about_Phthalate_plasticisers

33 Zhang LD, Li HC, Chong T, Gao M, Yin J, Fu DL, Deng Q, Wang ZM. (2014)

Prepubertal exposure to genistein alleviates di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate induced testicular oxidative stress in adult rats.

Biomed Res Int; 2014: 598630. doi: 10.1155/2014/598630.

34 Kay VR, Bloom MS, Foster WG. (2014)

Reproductive and developmental effects of phthalate diesters in males.

Crit Rev Toxicol; 44(6): 467-98.

35 Pflieger-Bruss S, Schuppe HC, Schill WB. (2004)

The male reproductive system and its susceptibility to endocrine disrupting chemicals.

Andrologia; 36(6): 337-45.

36 Mallow EB, Fox MA. (2014)

Phthalates and critically ill neonates: device-related exposures and non-endocrine toxic risks.

J Perinatol; 34(12): 892-7.

37 Pak VM, Nailon RE, McCauley LA. (2007)

Controversy: neonatal exposure to plasticizers in the NICU.

MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs; 32(4): 244-9.

38 Marie C, Vendittelli F, Sauvant-Rochat MP. (2015)

Obstetrical outcomes and biomarkers to assess exposure to phthalates: A review.

Environ Int; 83: 116-36.

39 Rusyn I, Corton JC. (2012)

Mechanistic considerations for human relevance of cancer hazard of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate.

Mutat Res; 750(2): 141-58

40 Tickner JA, Schettler T, Guidotti T, McCally M, Rossi M. (2001)

Health risks posed by use of Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) in PVC medical devices: a critical review.

Am J Ind Med; 39(1): 100-11.

41 National toxicology programm, the US department of health and human services (11/2006) Center for the evaluation of risks to human reproduction:

NTP-CERHR Monograph on the Potential Human Reproductive and Developmental Effects of Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP).

NIH Publication No. 06 – 4476.

42 Fachinformation Taxol (1/2009), Abschnitt 6.2. Brystol-Meyers-Squibb.

43 Panknin HT.

Particle release from infusion equipment: etiology of acute venous thromboses.

Kinderkrankenschwester. 2007;26:407-8.

44 Danschutter D, Braet F, Van Gyseghem E, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Van Bruwaene B, Moloney-Harmon P, Huyghens L.

Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and deep venous thrombosis in children: a clinical and experimental analysis.

Pediatrics. 2007;119:e742-53.

45 IARC (1997)

Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans.

IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 69:1–343.

46 Steenland K, Bertazzi P, Baccarelli A, Kogevinas M (2004)

Dioxin revisited: developments since the 1997 IARC classification of dioxin as a human carcinogen.

Environ Health Perspect 112:1265–1268.

47 IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans:

Polychlorinated Dibenzo-Para-Dioxins and Polychlorinated Dibenzofurans.

IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1997;69:1-631.

48 EPA 2012

Reanalysis of key issues related to dioxin toxicity and response to NAS comments

49 Bernard L, Décaudin B, Lecoeur M, Richard D, Bourdeaux D, Cueff R, Sautou V; Armed Study Group. (2014)

Analytical methods for the determination of DEHP plasticizer alternatives present in medical devices: a review.

Talanta; 129: 39-54

50 Fischer CJ, Bickle Graz M, Muehlethaler V, Palmero D, Tolsa JF. (2013)

Phthalates in the NICU: is it safe?

J Paediatr Child Health;49(9):E413-9

51 European Commission, T. S. C. o. M. P. a. M. D. (2002).

“Opinion on Medical Devices Containing DEHP Plasticised PVC; Neonates and Other Groups Possibly at Risk from DEHP Toxicity.”

52 Greenpeace International (2003) PVC-Free Future:

A Review of Restrictions and PVC-free Policies Worldwide.

53 Änderung im Anhang der REACH-Regulation (PDF), Stand 17. Februar 2011

54 REACH - Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation of Chemicals (2007)

55 RICHTLINIE 2007/47/EG DES EUROPÄISCHEN PARLAMENTS UND DES RATES

vom 5. September 2007 zur Änderung der Richtlinien 90/385/EWG des Rates zur Angleichung der Rechtsvorschriften der Mitgliedstaaten über aktive implantierbare medizinische Geräte und 93/42/EWG des Rates über Medizinprodukte sowie der Richtlinie 98/8/EG über das Inverkehrbringen von Biozid-Produkten

56 Emerson C (2010), ALP Australia Bans Phthalates in Toys.

57 Center for Health, Environment and Justice (2019), PVC: The Poison Plastic. PVC Governmental Policies around the World.

58 Referenz-Nr.: 9211/0506 DEHP als Weichmacher in Medizinprodukten aus PVC.

Erstellt: 22.05.2006

59 Health Canada. Consumer Product Safety. (2007) Proposal for legislative action on di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate under the Hazardous Products Act.

60 http://chm.pops.int

61 Japanese Makers to Switch from PVC to Eco-Based Containers’, Nikkei, Tokyo, January 14, 1998.

62 FoodBev.com, 31.01.2012

63 http://www.plasticsnews.com/headlines2.html?ncat=&id=24284

64 Health Care Without Harm (2003)

Glanzing Clinic in Vienna is First PVC-Free Pediatric Unit Worldwide.

Press release (June 13, 2003).

65 Initiative „Schadstofffreies Krankenhaus“ gegen PVC-haltige Medizinprodukte.

Deutsches Ärzteblatt, Ausgabe 15. November 2006;

66 OSPAR List of Chemicals for Priority Action (Revised 2011),

Reference number 2004-12;

67 Wirnitzer, U (2011)

Non-Clinical Testing of the Plasticizer Di-2-ethylhexyl-terephtalate (DEHT) under Clinically relevant Conditions.

ITO Symposium 15.-16. Sep 2011.

68 Wirnitzer U, Rickenbacher U, Katerkamp A, Schachtrupp A.

Systemic toxicity of di-2-ethylhexyl terephthalate (DEHT) in rodents following four weeks of intravenous exposure.

Toxicol Lett. 2011 Aug 10;205(1):8-14.

69 Unpublished data, Eastman Chemical Company.

70 https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/?set=ENV-FCN

71 Stoffers, N.H., Stoermer, A., Bradley, E.L., Brandsch, R., Cooper, I., Linssen, J.P.H., Franz, R., 2004.

Feasibility study for the development of certified reference materials for specific migration testing: Part 1. Initial migration concentration and specific migration.

Food Addit. Contam. 21, 1203–1216.

72 Stoffers, N.H., Brandsch, R., Bradley, E.L., Cooper, I., Dekker, M., Stoermer, A., Franz, R., 2005.

Feasibility study for the development of certified reference materials for specific migration testing: Part 2. Estimation of diffusion parameters and comparison of experimental and predicted data.

Food Addit. Contam. 22, 173–184.

73 European Pharmacopoeia monograph 3.1.4 of the Polyethylene without additives for containers for preparations for parenteral use and for ophthalmic preparations.

74 Kaiser J., Krämer I.

Physicochemical stability of diluted trastuzumabinfusion solutions in polypropylene infusion bags.

Int J Pharm Compounding 2011 15:6 (515-520).

75 Menard C., Bourguignon C., Schlatter J., Vermerie N., Schlatter J.

Stability of Cyclophosphamide and Mesna Admixtures in Polyethylene Infusion Bags.

Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2003 37:12 (1789-1792).

76 Arsène M., Favetta P., Favier B., Bureau J., Favetta P.

Comparison of ceftazidime degradation in glass bottles and plastic bags under various conditions.

Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2002 27:3 (205-209).

77 Jenke D, Couch T, Gillum A, Sadain S.

Modeling of the solutioninteraction properties of plastic materials used in pharmaceutical product container systems.

PDA J Pharm Sci Technol. 2009 Jul-Aug;63(4):294-306.

78 Römpp Lexikon Chemie, 9. Auflage 1992